*all quotes from Knowledge in a Nutshell: Carl Jung except where noted.

#1) ART as Inner Process

Loki / Hephaestus wood carving by C G Jung

During the period described as his Confrontation with the Unconscious (approx. 1911-13), Swiss psychological pioneer Carl Gustav Jung engaged in an inner dialogue and turned the resulting images into works of art. Materials from dreams and waking images were given concrete form and in doing so his inner conflict was transformed. He began with simple daily mandalas drawn in pencil (sometimes simply on his office stationary) progressing later to carefully constructed watercolours, oil paintings and gouaches. Jung’s Red Book is a testament to his dedication to serving the unconscious and it is striking to behold. Throughout his life he continued to turn his inner figures into outer works of art, carving wood and stone, painting and drawing.

“The images of The Red Book: Liber Novus depict quite exactly what this experience was like for Jung. Seeing his artwork up close, one is struck by his dedication to the inner world. Art historian Jill Mellick observed that, throughout it all, he gave ‘primacy to the process’, and he valued ‘direct inner experience’.” – p. 11

Jung “used the process of making art to allow his hands to unfold what the ego resisted – and discovered the power of creativity as healing work. With an attitude of play, Jung held the tension between the emergent inner voice and the ego. Out of the well-held inner dialogue, something new emerges: a new understanding, a new attitude or a symbol.” – p. 115

#2) From FREUD to BILL W.

Alcoholics Anonymous founder Bill Wilson

The profound conflict that Jung endured during his Red Book period was begun by his split from his mentor and father figure Sigmund Freud. While until his death Jung publicly celebrated the achievements of the founder of psychoanalysis, their intellectual division was a deep and profound one. While Freud saw much of human spirituality and creativity as driven by repressed sexuality, Jung saw the spiritual drive as an opposing pole to instinct within us. It was the dedication to a spiritual principle that made Jung so important to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous. As detailed here*, Jung’s work with an alcoholic patient and his direct assessment, both of the near hopelessness of the case and the necessity of a spiritual rebirth for healing, would come to be pivotal in the work of Bill W and the 12 step formula.

“His craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God.” –

Jung’s letter to Bill W*

#3) The SELF: Our Nature As Living Purpose

The primary insight of depth psychology (Freud and Jung) was the revelation of the existence of the unconscious. For Jung the unconscious was not only contents that are active within us but the matrix out of which consicousness developed. The ego is the tip of the iceberg, the unconscious the bulk beneath the water and the structure which gives birth to consciousness itself. Jung saw a purposive unitary force guiding this growth which he called the Self. He saw the Self, like many of Nature’s systems, as inherently self-correcting.

“As with the nautilus, whose shell repeats its spiral form while growing larger, nature preserves our inherent pattern while spurring our transformation. There is an instinct within living systems to endlessly renew themselves while maintaining the integrity of their unique structure. In our personal lives, the Self is the blueprint of our potential unfolding and the path to greater unity of the conscious and unconscious in us. Jung saw it perpetually reorienting us towards balance and guiding us into greater wholeness. Like many of nature’s systems, the psyche is self-regulating.” – p. 102

Images of this self-regulating function within us include the mandala and other centred religious and contemplative icons. That we would find this process living within us, slowly knitting consciousness and unconsciousness together in our dreams (and outer lives), is a revelation. It is the disovery of purpose active within us.

“That the unconscious would produce moving, powerful compensatory symbols inside us at all points to a fact that our culture may still not have fully grasped – that there is a force working within us which is always driving us towards healing growth and greater consciousness.” – p. 37

#4) The SHADOW

“Jung saw the shadow as a place of potential value. Our folly can become a source of wisdom if we can face it squarely and see it for what it is. Each person’s shadow is different, which makes shadow integration somewhat hard to describe. All of us may have different areas in which we need to grow, or aspects that we need to integrate, but there are general ways of understanding the process.” p. 86

There is a general usage in which the term ‘shadow’ refers to anything that is unconscious within us, but Jungians use that term in a more specific way describing an inner counter figure within us whose character is often the opposite of our outer persona and who is constituted by opposing values. The classic literary illustration of this living dynamic is Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in which a daytime good doctor who always does what is right and what is permitted by society is hounded by a nightime bad man who does what he wants and desires (the 1941 Spencer Tracy version is a particularly captivating film portrayal). This pairing is echoed in the writing of JRR Tolkien’s figures of Frodo/Bilbo and Gollum. Frodo and Bibo have the humility and goodness to avoid falling to the corrupting influce of the Ring of Power that they bear. Gollum represents our compulsive, addictive unconscious desire for such power.

Gollum, from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings

“Hearing the voice of the shadow brings discomfort; it is our inner opposite, something with which we will always disagree. Although connection to it and even a healthy integration is possible, we never settle into an accord with it. Throughout Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the protagonists of Bilbo and Frodo maintain a relationship to the split-off shadow figure of Gollum. They resist the desire to kill Gollum, and his partnership with them contributes to the successful resolution of their quests” - p. 91

One can look towards one’s opposite through the lenses of personality type, archetype or other personality profile systems for clues of our shadow. What values do the type that is opposite you possess? The varying essential qualities of the tarot are good potential illustrations of shadow – are we missing Strength? Judgement? The Fool? The Magician? Each of these could be a quality that doesn’t come easy for us. But most often, we’re able to come to see our shadow in the areas of life in which we are the least fluid, the least capable, the least easily able to navigate.

“I once knew an old lady who was very aristocratic and noble, and who conducted her life according to the most exquisite ideas of refinement; but at night she would dream about drunkenness, and in those dreams she herself would become hopelessly intoxicated. And so one must be what one is; one must discover one's own individuality, that center of personality, which is equidistant between the conscious and the unconscious; we must aim for that ideal point towards which nature appears to be directing us. Only from that point can one satisfy one's needs.” – Carl Jung, “Talks with Miguel Serrano“, C.G. Jung Speaking, p. 463

To begin to move toward that inner center – to become more whole – requires first the admission that something is missing, the allowance for our own imperfection. Unfortunately Western culture (and others) tends to push us to feel that we need to perfect, to be everything and that can make the shadow inadmissible. To integrate the shadow and come to see that living Other in us is a moral challenge. Jungian Online team member analyst Elisabeth Pomès described her process with her shadow this way:

“I felt at first that acceptance [of the shadow] meant agreeing with those parts of myself. Gradually I came to realize that it was not the case: accepting and recognizing meant making those aspects of myself conscious. It did not mean necessarily liking them or condoning them but accepting that they were there.”

#5 ) AGENT 488

“In 2003, it was revealed for the first time that during the height of World War II Jung was recruited by Allied Intelligence to provide psychological profiles on Axis leaders for them. He was Agent 488 for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the American wartime intelligence agency. An analysand of his, Mary Bancroft, was recruited by OSS leader Allen Dulles to be a sometime go-between. He warned that Hitler was a psychopath and should not be underestimated, and his reports were read by General Eisenhower. Dulles later said: ‘Nobody will probably ever know how much Prof. Jung contributed to the allied cause during the war.’”

While the emphasis is placed in Jung’s work and in the Jungian world on the inner search for one’s own shadow, throughout his life Jung also demonstratd the importance of confronting shadow in the world. Confronting collective, social and interpersonal darkness is a moral necessity and a kind of initiatory process by which one attains true adulthood.

Images from Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings series

In Answer to Job, Jung posits that the function of creation is a laboratory for the increase of consciousness not just in ourselves but the the world itself (or one could say in God). We do that not only through inner work but through moral action (and one might say also through love). Confronting social darkness is a wholeness bringing work.

“Confrontation with the archetypal shadow means seeing the reality of evil in the world in broad daylight; not looking away or going immediately into denial (as may happen automatically).” – p. 67

#6) ANIMA-ANIMUS • Inner Companion

The word anima is Latin for soul and Jung saw people us having an inner companion figure whose purpose it was to guide us more deeply into ourselves.

While the contents of the Anima and Animus (images, thoughts, affects) are personal, the archetype itself and its role as mediator to the collective unconscious are not personal. These inner figures direct us towards a greater relationship to the unconscious and the Self, but they can do so only if we relate to them consciously. – p. 167

Of course, before we can relate to these powerful inner figure consciously we project them outward onto others.

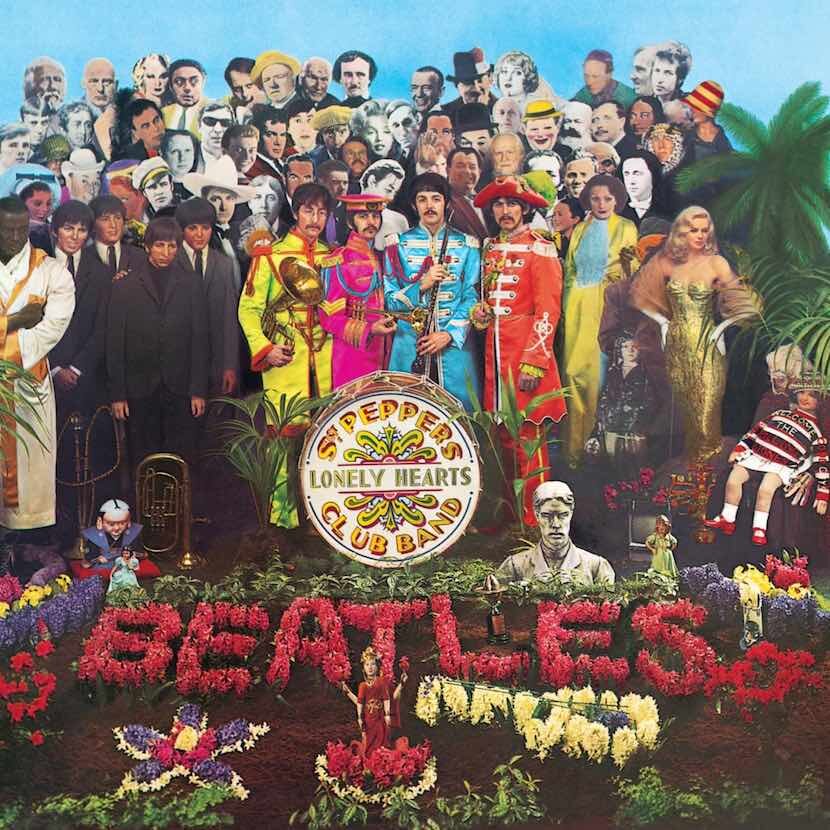

Patty Boyd with George Harrison in the 1960’s

When we are children, the Mother or Father may hold for us the Anima or Animus image. As we grow, we first experience it when we fall in love. Often, especially with love at first sight, we project our Anima or Animus onto the person we love. When the Anima is projected, we are in adoration. Because of this archetype’s timeless quality, the person with whom we fall in love may seem to remain the same age and always seem ‘just as beautiful as the day we met’. Anima fascination is frequently expressed in art and, for example, in songs such as ‘Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic’ by the Police or Eric Clapton’s ‘Layla’ and George Harrison’s ‘Something’ (apparently written for the same woman, Pattie Boyd). Here, we see the Anima as obsession, and very much beyond our control.

The powerful compulsion of these inner figures points to their potential for creative transformation and healing. The same energy that drives us into compulsive obsession can fuel us to creative heights and deep personal growth. This process is shown famously in the life of Dante Alighieri, author of The Divine Comedy. At the age of nine, Dante met Beatrice and was immediately captivated: ‘Behold, a deity stronger than I; who coming, shall rule over me.’ Marie-Louise von Franz noted that Beatrice is the figure who eventually leads Dante up to Paradise, but this happens only after he has spent a long time in Hell. Before the Anima figure leads him into contact with the timeless figures of the unconscious, it first puts him ‘into a hot cauldron where he is nicely roasted for a while’. – p. 87

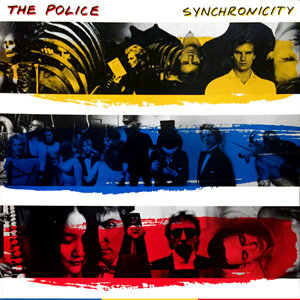

#7) SYNCHRONICITY

Jung gave us much of the language that we use today to describe psychology. He coined the terms: ‘complex,’ ‘extravert’, ‘introvert’ and others. He also gave the word ‘synchronicity’ to describe his persistent observation of remarkable and improbable moments of meaningful correlation of outer events with inner states. In parallel to many indigenous and mystical tradiitions, the worldly reality of synchronistic events is perhaps most thoroughly described in the ancient Chinese Tao Te Ching - the founding document of Taoism. Taoism believes that inner truth, authenticity and humility can have an effect on how events unfold. When we move through the world with authenticity we invite a better outcome for ourselves and others. In European tradition, teachers such Albertus Magnus talked about the power of emotion, especially strong feelings, to bring outer events into form:

“Often synchronistic occurrences happen in situations charged with emotion, with affect, with feeling. Perhaps you run into a past lover travelling on the same path you had previously travelled together; and then you realize that you had taken that same trip with each other ten years before, to the day. Synchronicities often reflect powerful emotional realities inside us and suggest that we live a world that seems built for them to happen, that values them and brings them into being. Appreciating them opens us to a wider worldview, one in which reality is full of meaning and that somehow spirit really is in matter.” – p. 192

#8) (K-)POP Culture

Today, the international Jungian community is an organically growing worldwide phenomenon. Unexpected outgrowths of interest have popped up outside the English-speaking world. You may not be aware that Jung and Freud are very popular across South America; both are taught in college and analysis is commonly undertaken. In Asia, China recently hosted a conference attended by three thousand people, and Korea has a Jung Institute of its own. Perhaps most remarkably, Jung’s work bloomed anew in the creative expression of the popular K-pop band BTS. Their album Map of the Soul: Persona was based on a book by the Jungian analyst Murray Stein and it explores their own struggles of identity. Their album was such a chart-topper that it drove Stein’s book back onto the bestseller list.

BTS promo shot for the Persona album

9) JUNGIAN ANALYSIS

In the most general sense, Jungian Analysis consists of two phases. In the first phase, the development of healthy ego is supported and in the second stage the unconscious is confronted. The relationship between the analysand and analyst is what helps to make both phases successful. In order to help facilitate this process, Jungian analysts are not only given extensive clinicial training, they enter into the process themselves as an analysand.

“Studies in attachment theory and other schools of modern psychological thought are part of the training of today’s Jungian analysts. . . . Analysts are trained at Jung Institutes worldwide, and those who undertake this training are typically over 40 years of age and usually have a graduate university degree. Candidates for training must also have completed 100 hours of personal work with a Jungian analyst before beginning. Once they are accepted into the training programme, they must complete approximately another 350 hours of their own personal work. While the training of Jungian analysts also includes a tremendous amount of clinical work and academic education, on a par with most clinical psychological doctoral programmes, its emphasis is upon wrestling with one’s own material, and that makes Jungian analysts different from other psychologists.” – p. 93-94

Since 2011, Jungian Online has been enabling those who want to begin this process to do it via live video. In a world where so many are digital nomads or far away from an analyst’s office, video sessions open up the possibility of working with someone who feels best for you and who is available no matter where you are. We’re happy to have a tremendous staff of analysts, clinicians and authors for you to choose from - check out our team bios here and to begin the process complete our New Client Introduction form here. We do our best to match you with someone suited to you or you can choose who you’d like to work with yourself. We also offer live events and classes, sign up for our email list to not miss out and please join us for the upcoming . . .

#10) JUNG 101 - Begins Oct. 8

Beginning Oct. 8, Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell author Gary S Bobroff MA is leading an Introduction to Jungian Psychology course that is intended for everyone. There are two meeting times each week (to faciliate attendence for time zones worldwide). We’ll meet weekly on the Zoom live video platform and reflect on a chapter of this easy-to-read book. We’ll look at the Shadow, Inner Work, The Self, Personality Types, Archetypes and more. Each week Gary will offer a presentation (45 min) and lead discussion on a chapter topic (30-40 min) and all sessions will be available on video afterwards. No experience necessary - this course will be led in an accessible and jargon-free way. You’ll get to share your thoughts, hear others experiences and ask questions of qualified Jungian analysts and scholars. Gary is thrilled to have outstanding special guest Jungian analysts joining him and the course is on sale now - to register or for more info please see here. Thank you! And for more on Gary’s new book Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell and the Intro to Jung course, watch this video: